Only Moving Forward: A Retrospective of The Last of Us Part II

Let’s get my bias out of the way: I am a huge fan of The Last of Us. It’s a good game - perhaps some of the best storytelling in gaming and the way the gameplay fits into the narrative and the worldbuilding is some of the sleekest game design in the modern age. And that’s a weird thing to say because The Last of Us is over 10 years old now.

The sequel builds upon that foundation in a stellar way. None of the new additions, be they new things to craft or new enemy types, feel out of place. Everything feels natural to a point, although it is odd there’s way less traversal puzzles that so littered the first game. To continue our bias reveal, I am also a huge fan of the Last of Part II for these and other reasons that should become clear by the end of this article.

I didn’t play the remaster, also this picture is too small, sorry.

But this isn’t a review of The Last of Us Part II, since I don’t do reviews, at least not simple straight up reviews like “is the game good?” There is a ton of discourse about this particular game, a lot of it is bad faith in nature due to whatever political argument you want to make (I will not be elaborating) and some of this spills over to critiquing the artistry of the game to support those bad faith arguments.

I want to critique something different, break it apart, and see if it fits into the overall scheme that the Last of Us sets to establish through both editions of this franchise. I want to focus on something I noticed, something my wife noticed, and maybe something you might have noticed as well if you have played through the game. What I want to focus on is - why do we never have to nor can we choose to go backward in The Last of Us?

Potential spoilers ahead for those who have never played these games or watched the HBO show.

Only Moving Forward

There’s not some sort of trick being pulled on you here, I mean it very literally. Throughout The Last of Us and its Part II sequel, we as the player must navigate a post-apocalyptic, dystopian future of a world ravaged by CBI, the Cordyceps Brain Infection. We do this through different characters - Joel, Ellie, and Abby, but the modus operandi remains the same no matter who we pilot: loot everything, stealth as much as possible, eliminate every threat.

This is the core gameplay loop of The Last of Us. Gather supplies to craft weapons that might make combat easier. Stealth our way through enemies and choose whether or not to engage them silently or loud. Spend resources dispatching said enemies. Loot the combat zone for the next group of enemies. And so on.

If you don’t say “Ah yeah, pills!” every time you find them, they don’t work right.

While we engage in this loop, the settings change, the environment switches, the situation differs, but the loop maintains as the gameplay only exists to serve and reinforce the story.

[Writer’s note: I would never claim that the gameplay is lesser than the story - there’s entire modes dedicated to just this gameplay loop with no larger story attached and there’s a community out there that support that the gameplay loop is fun to some people (I am not one of these people - while I respect the game design and what it adds to the narrative, these games make my heart race like the wee little baby I am).]

A crucial part of this gameplay loop exists within the transition between these environments, the navigation from zone to zone be they loot zones or combat zones. The characters in these environments must bend and contort their bodies to access the next bit of the gameplay loops through crouching or going prone and crawling or climbing or squeezing their way through small gaps in walls in such ways that make the journey feel real; it takes energy to move from place to place like it does in the real world.

Another crucial part of this gameplay loop is that the navigation only goes in one direction. The Last of Us is in no way an “open world” game. I’d fail to describe anything about these games as “open” at all, except maybe you should “open yourself up to some heartbreak.” Cause your heart’s gonna break. It will. And if it doesn’t, let’s never meet.

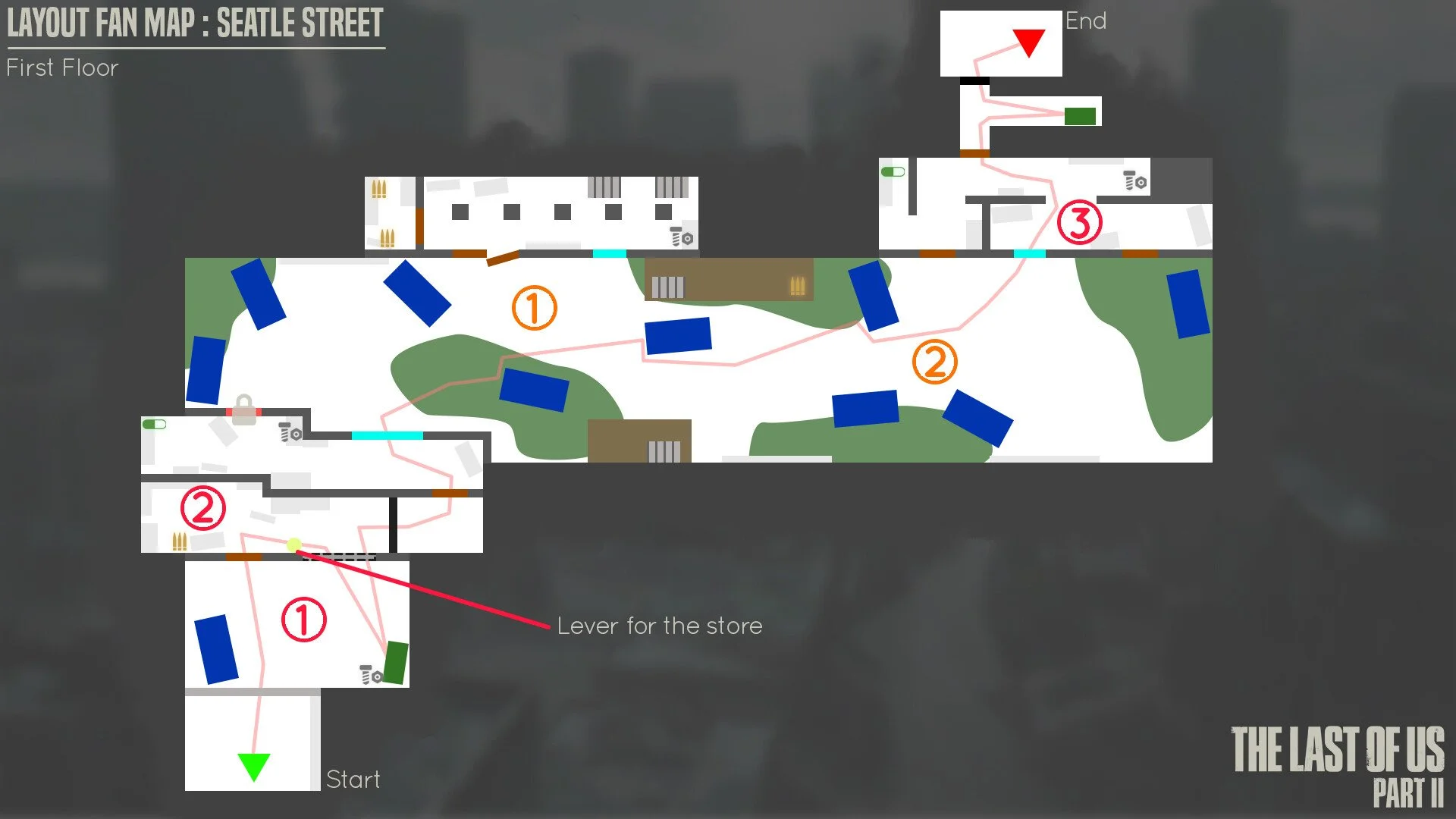

This segment in Downtown Seattle on Ellie’s first day is as open as it gets.

Each environment is carefully sculpted, each piece of loot you pick up has to conform to some real world logic. Go into a bar? You’re bound to find alcohol. Raid a laundry room? Here’s some rags. The detail to real world placement of these items is something I grew to expect and respect - there is a lot of attention to detail of the placement of things, of the places we navigate, of the set dressing that brings this world to life.

Which is why there are some pretty jarring moments for me where the characters simply abandon one of the biggest rules of survival pretty much constantly in these games, which is: Always have an exit. A second rule of survival is very much related: Never go anywhere you cannot come back from. There are story scenarios where a character says they are just going to go look around or explore a potential route that result in the complete cutting off from the route that lead them to that point and that shit should be terrifying.

The closest example we have in the real world of the type of exploration done in the Last of Us would be the modern practice of urban exploration (or urbex, if you’re in the know). While there are larger rules in the urbex community like “Take only pictures, leave only footsteps” and “you are going to be trespassing on private property no matter where you go,” there are also a few common sense guidelines that echo the sentiments I’ve expressed here. Do not go somewhere you cannot come back from and always plan your route (with the implication that you know where the exit is at all times).

These guidelines help people stay safe in a world without fungus infected zombies so they should absolutely be followed by our various playable protagonists, yet not even Abby, who was trained in the most strict military protocols and survival techniques, adheres to them.

And when every other detail in this game serves to make the setting and the gameplay and the narrative feel as real as possible, why is it that this decision of throwing caution into the wind for the sake of reaching one’s destination is made time and time again?

It’s Gonna Suck When You Have to Come Back

In the gameplay segment or chapter known as Seattle Day 2 for Abby, we are introduced to the concept of a skybridge built by the Serphites for traversing around the WLFs. If that sentence didn’t make sense to you, you’re too deep into this review and I’m sorry. Abby, who we are playing as, has an established fear of heights. This is reinforced in the gameplay as Abby when you approach any sort of ledge that is high up. The camera zooms out and in and the further you look down, the further the image shifts and becomes blurry as though Abby is experiencing vertigo. Because she is. It’s really cool and if you didn’t notice it, go check it out.

For plot reasons, Abby must get to a hospital by navigating these skybridges and we undergo a very long transversal section of gameplay where we are making our way across what is extensively a system of construction cranes and scaffolding loosely held together to form a bridge over the landscape of foggy downtown Seattle.

Now, I play these games while my wife watches because she is engrossed by the story of The Last of Us and occasionally she will offer very good comments on what is happening in the game. On this occasion, seeing how much Abby is affected by the drastic heights she is crossing, my wife said astutely, “It’s gonna suck when you have to come back this way.”

To which I said, “Oh, you sweet summer child. We will never go back.” This, of course, prompted some confusion, but what I meant was, not once in the history of me playing The Last of Us has the game ever made us return somewhere we had been before. Travel like that is reserved for cutscenes. There might be a short scene of our character hopping into some vehicle that can explain our expedited return, or sometimes we appear just in front of our home base after a quick fade to black transition.

An example of the Last of Us level design.

To prove my point, Abby doesn’t even completely cross the skybridge. She freaks out, slips, and drags her guide Lev down with her falling luckily into the pool of the hotel they were crossing to. This prompts an extended sequence of navigating our way through an infested hotel with crumbling floors and a sequence of jumps we cannot make in the opposite direction as if to reinforce that we will never be coming back in this direction.

Because we won’t. We never will. The Last of Us is a game played in one direction both in terms of time, traversal, and in player agency. It’s almost as if this “One Direction” motif was a core tenement of the design, writing, and production of the game. No backtracking. No player choice when it comes to narrative. No alternative routes. The game will guide the player through a series of challenges, scenes, and traumatic violence at the pace we have designed.

And if we have to fly in the face of common sense and survival rules to accomplish that pace, then so be it, we have some fictional lives to ruin, damnit, stop showing me survival guides and urban exploration rules.

The Complete Discography of One Direction

In a way, I very much like the design choice that this “one direction” design philosophy that The Last of Us clearly has. We don’t have to worry about missing too much other than when you accidentally find the loading zone to the next segment before you’ve convinced yourself you have explored everything.

There are two moments in the Last of Us Part II where I was screwed out of opening a safe because I accidently stepped too far away from it and triggered a cutscene or a “press triangle to open the door” moment. The first time it happened was on Seattle Day 1 as Ellie where I thought maybe I could come back upstairs to the very first safe in the game once I found the combination to open it. I never did find that combination and apparently you can crack the safes by feel so maybe I never needed it.

The second time it happened was Seattle Day 1 as Abby onboard the Washington ferry. After I had cleared out the top floor of the ferry of the infected there, I stumbled across another safe but with no note or clue as to its combination. I looked around a bit and found a door and without thinking, I went to open it thinking that the combination would definitely be on a note on the other side. But the door slammed shut behind me and a filing cabinet was propped up against the door so I could never go back and search again for that safe combination.

Pictured: Something I will never obtain.

These two moments and any loot I missed out on are the casualty of the One Direction movement, but I’d like to think that they play very much into the overall vibe that the game is going for. Would Abby really stop and look around every nook and cranny for a note to open a safe on a ferry when she’s so close to the aquarium, where she suspects Owen is after he went AWOL? Likely not.

A joke I like to make about the HBO show The Last of US is that my favorite scene in every episode is when Joel and Ellie reach a new building, they take twenty minutes to scour the place for scissors and duct tape. Because that’s how I play. It’s the little bit of player agency we get in these games - we get to decide every aspect of the core gameplay loop. But it’s not our story. It’s Ellie’s. And Joel’s. And Abby’s. We have no influence over the direction of the story, just like we have no influence over the direction of our navigation.

Ready Player None

I’m gonna do our first ever Heading 2 here to interject a critique I see time and time again about why The Last of Us 2 is bad, but the Last of Us 1 was good and it has a lot to do with a term I’ve casually thrown around here and that term is “player agency.”

Player agency is a concept in narrative based games of the modern era where the player has some influence over how the story plays out based on the choices they make over the course of the game. Mass Effect and Dragon Age where huge forefathers of the modern version of our understanding of player agency, but the concept’s been alive way before those examples in the genre of CRPGs like the original Baldur’s Gates, classic Fallout, and of course, Tokimeki Memorial.

Player agency can also be understood as the influence a player has over a game and be more widely applied to all video games ever. Mario doesn’t run without player agency. Mario is influenced by the player to run. To jump on Goombas. To select what levels to play and which to skip, etc.

This understanding of player agency has fallen out of the wider parlance when we talk about video games today in favor of the more modern understanding that when we talk about player agency, we’re talking about narrative choices that can affect the outcomes of a story.

With that understanding, The Last of Us has zero player agency when it comes to the narrative. In both games. There are no decisions that you as the player get to make that affect how the story plays out. The story will play out the same every single time.

The crux of this is the climax of The Last of Us Part I. Joel delivers Ellie to Salt Lake City to the care of the Fireflies who have a way to create a cure for CBI. Tess chooses to inform Joel that it will cost Ellie her life. Joel decides to save Ellie by any means necessary and guns down many, many Fireflies in the process, including Dr. Jerry Anderson, the man with the idea for a cure.

Pictured: The man who will save the world

The rest of the Last of Us franchise stems from that decision and that decision alone. Everything before that decision, the entire journey of getting Ellie to Salt Lake City and seeing Joel bond with Ellie, grow closer to her, consider her his daughter, all builds up ultimately to this decision. It is the only decision that Joel can make given everything he has done up to this point.

It just so happens that this decision is also one the player can get behind. We feel justified in saving Ellie because the Fireflies never bothered to explain to Ellie that developing a cure would mean her sacrifice. She would die never knowing that she was helping people.

So, and I’m speaking in a supposing manner now, I think a lot of people had no problem with Joel’s decision to rescue Ellie and take her back to Jackson to live out what meager life they can. It should be shocking. It should shock a player to their core because this is the first and only time in The Last of Us where you gun down innocent people who have done nothing wrong. The only thing the guards you kill trying to save Ellie are guilty of is showing up for work that day. Joel has a shady past and might have killed some innocents before, but that’s before the game started. That’s in his backstory. We’ve never controlled Joel doing something this close to evil before.

The Last of Us Part I ends in what should be a fascinating disconnect between what the game is asking us to do, kill innocent people to save Ellie, and what we want to as the player. But I think we as a player base got too caught up in wanting to save Ellie to stop and reflect on our actions in those moments, in what saving Ellie truly means - the abandonment of hope for a cure, the rejection of a return to normalcy.

It makes perfect sense to me, then, that The Last of Part II is chalk full of these moments and that every one of these moments is a perfect logical conclusion and progression of the one moment in the previous game. What serves as the climax for The Last of Part I is but the tip of the iceberg in Part II.

Ready Player None-r

If every moment of banter, traversal puzzle, and each time Ellie saves you with her pocket knife ultimately serves the purpose of justifying Joel’s decision in The Last of Us Part I, then every moment of combat, cutscene, and banter between Ellie and whoever she’s with in The Last of Part II is to solidify that your motivations are monstrous. The main sentiment of Part II seems to be that revenge and retribution are violent means to unnecessary ends that destroy lives. This is true of both Ellie and Abby’s story - by the end of each of their segments, they have lost everything for the sake of revenge and retribution and it is only when they choose to break that cycle do they begin to heal.

We have 20 hours of gameplay to explore this theme, so let’s start out with Ellie having to kill a bunch of combat dogs that trigger the most gut wrench reactions from the NPCs who we will also be killing. The first thing I noticed in the early hours of Ellie play is that every NPC seems to have a name and people cry out this name as you kill their friends.

Also, I had to verbally apologize to the dogs I was killing as I was killing them because I did not want to kill dogs. Please stop making me kill dogs. Why did I have to kill so many dogs, Naughty Dog? Is this your sick, sick joke, you twisted fuck? Ahem.

Why yes, it is their sick, sick joke and the punchline is: Ellie isn’t the good guy here. Just like Joel in the final sequence of Part I, Ellie is killing somewhat (it’s very grey) innocent-ish people who are just trying to live their own lives (read: do a genocide on another group of people).

And the game highlights this in super close-up, highly graphic, and deeply upsetting ways. When we switch to Abby and we’re attacked by Serphites (yes, I use the proper term), this burden of killing innocents is eased slightly. Abby doesn’t kill dogs and she was attacked first, so it feels okay. Then, in the third act of Abby’s story, she begins killing her fellow WLFs to protect Lev. Her story sort of mirrors Joel’s in a way. But Abby becomes the monster that Joel was when he wanted to save Ellie. Abby’s actions result in the death of Isaac and probably ultimately the disbandment of the WLFs (or at least a huge disorganization of them that will lead on to strife and discord) - she has become what she hated so much in Joel.

My point is, the narratives of these games are set up in a way where every individual element of storytelling and a large chunk of the gameplay reinforces the outcomes we reach by the end of the story. To add in player agency at the storytelling level would be to drastically alter the chemical makeup of these games - it wouldn’t be The Last of Us.

If you like first the game for how the story is told and the way the game is, then you should ultimately like the second game, because it’s more of the same if not more of the logical conclusion of the first game. I’m not writing this article to convince anyone of this, I’m just stating an objective fact. The two games are the same construction, the same narrative design, and the same spirit - the only thing that differs is the message that each game builds to and the characters involved.

Let this be an end to “The Last of Us fell off” discourse.

One Way Ahead

It took me a long time to sit down and play The Last of Us Part II. What I thought was a pivotal emotional climax for the game was spoiled for me indirectly through an internet meme of all things. It took a long time after this spoiling for me to build up what I thought was the mental strength I’d need to see what happens.

It turns out, that moment I was so worried about takes place in the first hour of the game and is the impetus for everything that happens next. Even more so, when I learned who the perpetrator of the action was and their relation to the events of the first game, an inner peace glowed in me regarding the whole affair. Because it made sense. Because it was interesting.

Because from the onset of the incident there is only one option for Ellie to do, there is only one choice to make, and only one direction to go - we can only move forward. While I still have my misgivings about exploration safety and dystopian survival (I literally made sure all the doors I went through stayed open so I could run out if necessary), the design choice of only moving forward suits The Last of Us and its messages.

That being said, jumping backward to Abby’s three days in Seattle felt a little off pacing-wise and totally invalidates all 3500+ words of this article, so can we remaster the game (again) so that we play out those segments concurrently somehow?

Eh. Who am I kidding? We can only move forward. And I’m never playing The Last of Us again.