Back When Tigers Used to Smoke: On Beginnings

With the recent addition to our family, I’ve been thinking a lot about beginnings. Everything is new for my daughter, she didn’t come equipped with much more than the instincts to eat, sleep, poop, and cry when we aren’t taking care of one of those needs. To be inclusive, there are a few other holdout reflexes that babies come equipped with like the ever troublesome Moro’s Reflex that triggers when a baby feels as though they are falling, e.g., any time they are being actively lowered into a crib (it’s kind of funny, they flail their little arms out wide and then close them again). Other than these innate reflexes, everything in this dumb burning world is new to my daughter.

And that leads me to a big question - how does one start introducing the world to one’s kid? How does one begin that process?

A different kind of starting line.

Now, I’m not really asking that question and this piece won’t be about that much at all, it’s just a vehicle with elements of my personal life blended in to get at something neat that I had no other way to introduce, but uh, do you guys know how Korean folktales start? In English, we use this little phrase “Once upon a time,” to evoke a time long gone when magic and princesses mayhaps dominated the world, but I think the Koreans have us beat with their phrase, “호랑이 담배 피우던 시절.”

For any of you who don’t speak Korean (including me), here’s a more western spelling of that phrase: horangi dambaepiudeon sijeol. Roughly translated, this phrase means “back when tigers used to smoke,” or “In the time tigers used to smoke” and that’s just a badass way to start a story of any color. How did I go almost 35 years without knowing this? was my first reaction, I’m not sure what yours is, but together, let’s take a little deep dive into the various ways people start their stories and break them down to understand their meanings. Because that sounds fun to me and I hope it does to you too.

In the Time When Tigers Used to Smoke

Tigers are fascinating. Like the wolves that haunt a good number of western fairytales, tigers seem to have captivated an entire hemisphere of the globe with their vicious, stalking nature. Unfortunately, there is no recorded origin for the implication that they used to smoke, leaving us to speculate why they kicked the habit before we reached modern times.

There is one hypothesis as to the meaning of the phrase “Back when tigers used to smoke,” that carries on connotations of social hierarchy of the times. According to a user on Quora who goes by Neky (I know, I know), the “Cigarette was first introduced in Korea in 1618, roughly in the early 17th century. Back then, everyone could smoke. Even small children at 4–5 used to smoke. They didn’t know how smoking is bad yet.” Over time, namely during the Joseon period, the availability of cigarettes would become more restrictive, reserved for members of the higher classes, leaving out our poor striped friends. The phrase then evokes a time when everyone, even tigers, could smoke which no doubt felt like a long, long time ago for those who had to go without that sweet, sweet tobacco and nicotine.

Pictured: a badass.

Because of the nature of folktales being more of an oral tradition than a written one, I do not have a recorded first example of this phrase being used. It’s an interesting one, though, as it can only have existed as long as smoking was a popular pastime for Koreans, so we know it isn’t too much older than the 1600s. The funny thing about my exploration of the phrase was that I found the same exact wording of the Quora post in not one but two different articles about the phrase right down to the exclusion of the word “the.” So, if that user was wrong, so are those other two articles.

Other than this supposition, there’s not much in the way of an explanation for the origin of the phrase. Tigers are extinct in Korea today, unfortunately, as they were hunted for sport during the time of Japanese occupation. Korean tigers are still a large part of the country’s mythology, even playing a part in the creation of the country in one version of the myth. I won’t dive too deep here, we’re only interested in the beginning after all, but depictions of Korean tigers smoking are still ubiquitous to this day even with no hint as to how the phrase came to be.

There are other popular tiger related idioms in Korean that would suggest the practice of evoking these creatures was commonplace. “호랑이도 제 말 하면 온다” which translates to “Even a tiger comes when you say his name,” a phrase used to admonish children for not listening to their parents. There’s also “호랑이를 잡으려면 호랑이 굴로 들어가야 한다,” meaning “To catch a tiger, you have to go to a tiger’s den.” This one has been compared to “No pain, no gain,” denoting that you have to give something your all to accomplish it.

So tigers abound in the Korean idiom scene. There’s also way more idioms that have nothing to do with tigers, but perhaps the occasional to frequent appearance of tigers in everyday language colored the beginnings of folktales. Either way, it is no doubt one of the coolest ways of beginning something.

A Story, a Story. Let It Go, Let It Come

Ah, yes, and now we reach the part of writing the article where I’ve covered what I wanted to cover and now have to pivot to something else. I was going to keep deep diving into different folktale beginnings, but none are quite as neat as back when tigers used to smoke. Maybe we shouldn’t have started with that one and the truth of the matter is there aren’t a ton of sources behind the beginnings of folktales, their origins, or why they rarely seem to change.

There is a great exploration of the formulaic and flourishes found in folktales ‘round the world from Anothy Madrid in The Paris Review that I found intriguing and will be linking to somewhere in this sentence (surprise, it’s here), but I won’t be replicating any of his work here and instead instruct you to click that link and read his article, which is very good. I did lift one of the beginnings from that article for the heading of this section, but we don’t need to tell him that.

This opening, “A story, a story. Let it go, let it come,” comes from Hasua, a region, language, and people found all over West Africa. Apparently every story begins with this phrase and it is a beautiful phrase. Interesting is that the phrase evokes the story’s leaving before it even arrives, maybe emphasizing the temporary nature of our stories, how they only live with us during the telling and as long as we remember that telling. Let it go, I think is a gentle reminder that stories and memories will leave us eventually, that we won’t be able to recall them as we go about our lives and experience other stories. But the nature of the order of this phrase can be cyclical, I think, in that we might one day remember the story again (Let it come). It’s a very good way to start a story if not just an outwardly perfunctory way to let you know a story is happening.

I think, perhaps, in the same way, I may need to let this piece come and go as I have run out of steam here toward what could be generously described as “the middle” of writing through this idea.

Once

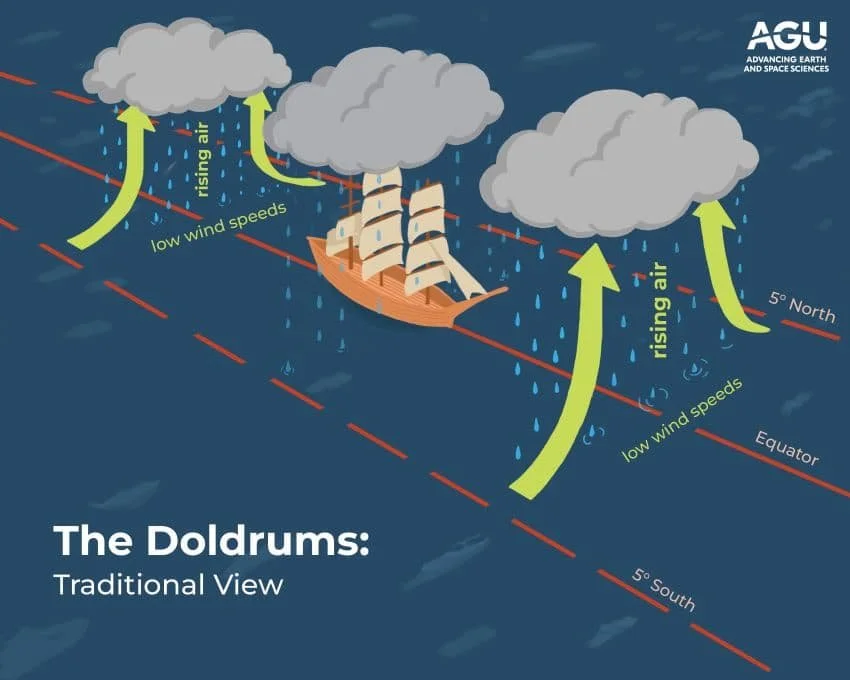

What I’m struggling with now, the doldrums that come when the first winds of starting something have died down, is why beginnings are so important. With the right energy that a good beginning breathes into a work, there’s enough momentum to carry us through the hard part, when inspiration and passion give way to the arduous task of following through. It’s easy to get wrapped up in starting something new, it’s fun even. I have so many projects that I’ve started and then left to rot on the vine as if projects like produce can ripen on their own without being watered, weeded, and w-cared for.

Creative doldrums are even worse; you’re not guaranteed rain.

One of the more common thrown around openings that I could not track down an origin for is the phrase “When the animals talked.” I even found a “When the animals and men spoke the same language,” but there was so much controversy surrounding this phrase as I could not find an actual country or language of origin for it. Spanish apparently has “Cuando los animales hablaban,” but Flemish fables also allegedly have their “Toen de dieren nog spraken” and neither of these languages or many others have true recorded examples of their first use, which makes it difficult to nail down if it was even used at all. Here’s a very fun internet argument from a Dutch speaker putting forth that the phrase is more of an ironic tongue-in-cheek phrase than an actual fable or fairy tale opening.

Regardless of whether the phrase was actually used to open folktales and fables, it is unquestionably a good phrase. “Back when the animals speak” evokes a time when the world was still new, when customs weren’t as set in stone, when magic could still be thought of as “in existence,” and for that I applaud it. The point of bringing this phrase up now, at the end of this post’s life, is to hopefully give you some inkling of a point to this discussion of beginnings and the way we phrase them.

Don’t suffer the doldrums for so long that your begun projects date back to when the animals could still speak or when the tigers used to smoke. Instead, use the winds from your beginnings to sail through the tough middle center and onto natural or unnatural conclusions.

It’s easier said than done, but let’s spice up the “saying” of it all to make it more fun.